Silicon Valley Bank (SVB), based in California, has a 40-year operating history and is one of the largest lenders to the Silicon Valley venture capital and biotech industries (estimated to have relationships with roughly half of Silicon Valley start-ups and high-growth companies).

The company developed a successful niche in lending to start-ups and growth-oriented companies (that were not yet profitable and had limited tangible assets as collateral). In conjunction with providing its lending services, SVB also housed these companies’ cash deposits, As the Silicon Valley landscape boomed over the past five years, SVB benefitted tremendously. Its clients (backed by venture capital firms) raised substantial amounts of cash to be custodied. As a result, SVB’s deposits rose substantially from $44bln in 2017 to $189bln by year-end 2021 while loans only increased from $23bln to $66bln. Unlike larger national banks or even regional banks, SVB’s deposit base was highly commercial as opposed to retail oriented. Commercial deposits are far less sticky than retail deposits (which proved to be one of the main factors contributing to SVB’s undoing). SVB invested heavily in Treasury and mortgage-backed securities to earn a spread on these deposits, especially during 2021. By YE 2021, SVB had $128bln in largely these types of securities. With interest rates near historical lows during 2020 and 2021, SVB attempted to earn higher yields by investing in longer-term securities. While these securities had no credit risk if held to maturity, they did have interest rate risk and would lose value on a mark-to-market basis if interest rates rose. During 2022 and 2023, the economic landscape changed significantly as inflation soared and the Fed rapidly increased interest rates. The value of SVB’s Treasury and Mortgage-Backed Securities declined on a mark-to-market basis (for instance, at the end of 2022, SVB had $91bln of held-to-maturity (HTM) securities on its balance sheet whereas their fair market value was actually $76bln. Accounting rules allow banks to hold HTM securities at par value rather than at fair market value for balance sheet purposes. In addition, SVB had $23bln in available-for-sale (AFS) securities as well. Since both the HTM and AFS investments bore no credit risk, the decline in mark-to-market values should not have caused any problems unless they needed to be sold in the open market versus holding to maturity to realize par value. During 2022, however, as valuations dropped for growth-oriented companies, venture-capital portfolio companies’ access to investor funding dropped significantly. In response, these companies began withdrawing their deposits at SVB to fund operations. Additionally, as corporate CFOs and treasurers searched for higher-yielding investments, companies also withdrew deposits at a faster pace than retail customers. Deposits declined from $189bln at YE 2021 to $173bln in 2022 and further declined during the first two months of 2023. As liquidity and cash balances were deteriorating at SVB, rating agencies informed SVB of likely downgrades to its outstanding bonds.

In response, SVB sold off its entire $23bln+ AFS bond portfolio at a $1.8bln loss to raise cash. They disclosed this unexpectedly and clumsily on a conference call on Thursday March 9th which shocked investors.

In addition, SVB concurrently attempted to raise $2.25bln in equity to shore up its balance sheet and enable it to continue lending at attractive terms to venture companies.

These steps only raised concern. Venture capital firms began instructing portfolio companies to promptly withdraw deposits from SVB. This led to a swift spiral of panic, and a classic run on the bank ensued.

SVB’s share price dropped by 60% to $106 on March 9th from $268 on March 8th.

Panic withdrawals continued on March 10th (a staggering $42bln was withdrawn in one day), and SVB had a negative cash balance of almost $1bln before being declared insolvent mid-day.

SVB’s share price declined by another 60% on Friday, March 10th before being halted as regulators seized control of the bank. Equity holders will likely be completely wiped out post the government’s intervention.

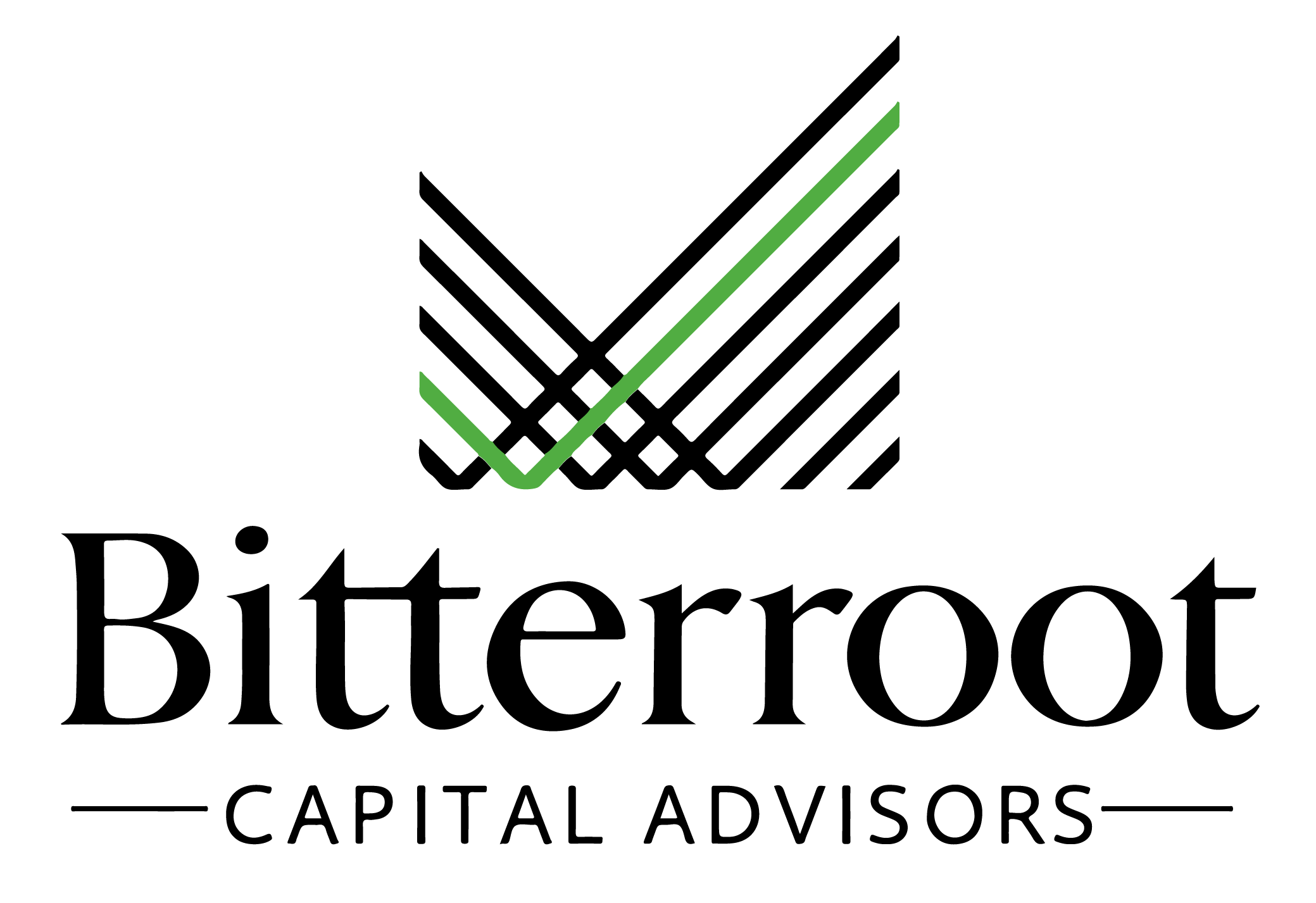

While SVB’s demise was sudden and shocking, its problems resulted from a fundamental failure in risk management. The business model had a classic mismatch between assets (large portion of investments in longer-dated securities) and liabilities (short-term deposits and less sticky given the highly commercial as opposed to retail deposit base). This was compounded by concentrated risks related to exposure to venture-capital and high-growth tech and healthcare companies. The chart below from JPMorgan illustrates SVB’s outlier status among banking peers in terms of commercial vs. retail deposits and high exposure to securities as a percentage of both assets and total deposits.

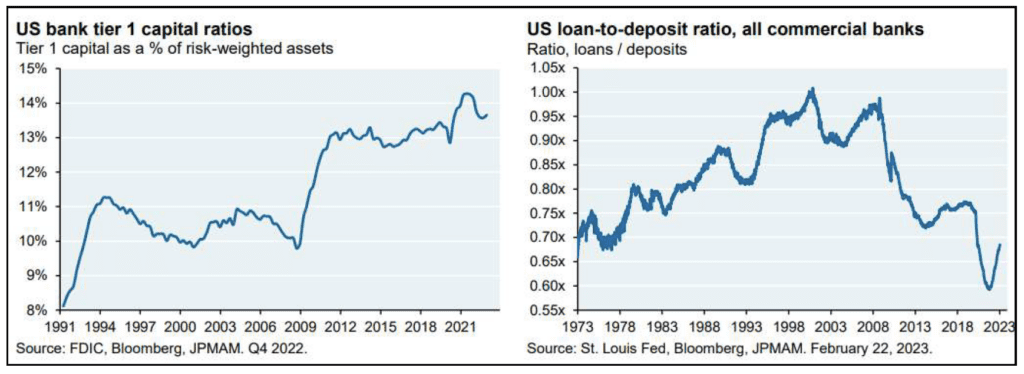

We do believe that SVB’s situation was largely isolated to a handful of banks. As seen in the charts below, the financial health of US banks is broadly very sound.

US banks are, however, sitting on $620blm of unrealized mark-to-market security losses. These securities bear no credit risk and will be realized at par if held to maturity. Thus, if banks are not forced to sell these securities, they are not required to recognize losses. Additionally, these securities would increase in value if rates were to decline. We would expect there to be pressure on deposits, as depositors withdraw funds to earn higher yields in other short-term, low-risk alternatives (e.g. Treasury Bills, money market funds). But, because most of the larger national banks as well as most regional banks have a lower-risk deposit base (majority are stickier retail deposits rather than commercial deposits), the risk of forced sales is low at these banks. The prospects for certain smaller regional banks with business models perceived as more like SVB, including Pacwest, First Republic, and Western Alliance, are more uncertain. It remains to be seen whether the government’s new facility program that guarantees deposits may assuage fears about these banks’ financial stability and whether it proves beneficial in maintaining calm in the broader financial ecosystem.